The genre of portfolios—from the portfolio “explosion” of the ’90s to their evolution into the ePortfolio of the early 2000’s—is reflective of changes in both the field of education and the world around them. By revisiting the portfolio in 2021, at a time when the world is experiencing both a global pandemic and a heightened awareness of racial inequality, this project attempts to predict what a new, emergent portfolio might not only value, but also look like. My teaching portfolio argues that teaching portfolios, as a genre, should always be reflective of a teacher’s biography and the world around them. This means that, while the structure might stay the same—a collection of essays, lesson plans, and evaluations—the content is different and more illustrative. It is an evolved or emergent version of the teaching portfolio that responds to a changing world, notably a Covid-19 world. In this world, Bettina Love—an abolitionist educator, scholar, and activist—argues “we have the opportunity not to just reimagine schooling or try to reform injustice but to start over.” I propose that we start over by making teaching portfolios—that privilege reflection, collaboration, and opportunities for feedback with a focus on design justice—a powerful tool that helps us decide who we want to do the work of starting over with.

In the spirit of that mission, the work that follows details my thinking as this project was and is emerging.

Where It Started:

As with all good stories and learning moments, mine starts with a point of tension that challenged my worldview.

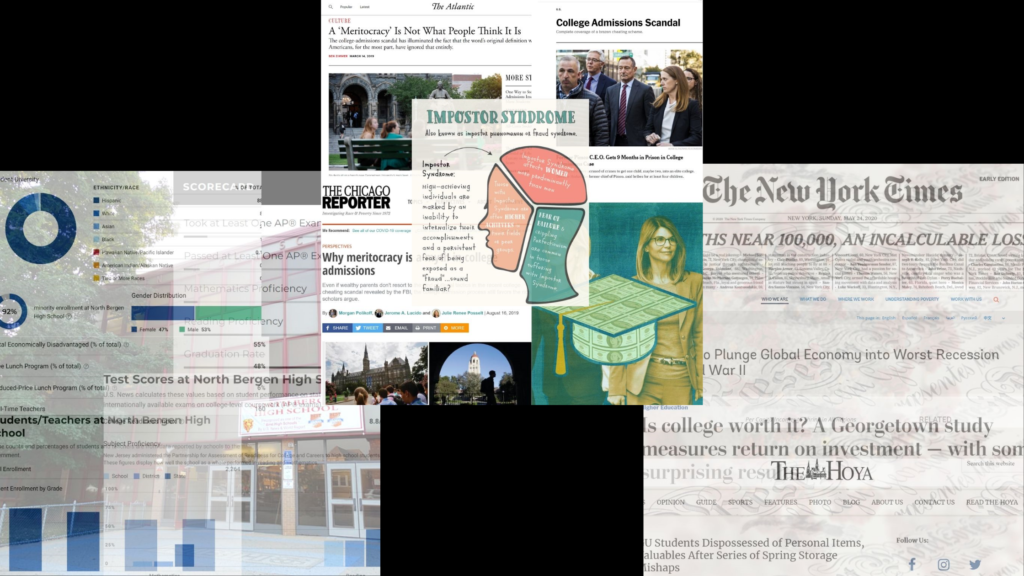

The first image to the right is a picture of my high school, North Bergen High School. If you look closely, there is a banner hanging on the front of the school. It reads: “Ranked on the best high school’s according to US News & World Report“. This is not true. According to the US News and World Report website—the images of which are laid over this picture—in my school: 55% of students are economically disadvantaged, college readiness is 8.8/100, and total enrollment is 2,264. In high school, as I prepared to—and was discouraged from—applying to college, I began to realize that the education system didn’t work the same way for everyone.

My suspicions were later confirmed in college when the college admissions scandal broke out my sophomore year—highlighted in the middle picture here—a scandal that my own university was involved in. In the college admission scandal, the Department of Justice charged 50+ parents of college students in what they called the “largest college admissions scam” that they had ever prosecuted. Dozens of parents paid millions of dollars to help secure their children’s spots at elite colleges and universities by falsifying exam scores and fabricating student biographies. While I struggled with imposter syndrome, it turned out that there were people on my campus who actually didn’t belong!

This tension between education, meritocracy, and me finally reached a boiling point when I graduated this past May— into a pandemic and global recession—leading me to think: “Okay, I have something to say about this whole endeavor. Why do people go to college? What promises does college make? Which promises does it actually fulfill?”

Where It Is:

At the same time that I was questioning the relationships between meritocracy and education, I felt complicit in reinforcing its ideas. As an educator, the majority of the students that I work with are from “nontraditional” backgrounds. I work to increase diversity, inclusion, and accessibility in education by validating students’ lived experience in academic settings, creating thoughtful course designs, and being an advocate for their success both inside and outside the classroom. However, as I continue this work, I am all too aware that this work attempts to shape students into “ideal” college students. I myself was one of these students. I chose to attend Georgetown because of bridge programs like the Community Scholars Program and the Georgetown Scholars Program which works to help students transition from high school to college.

Students are told they need to change to belong at colleges and universities. Take, for example, writing instructors who insist on the use of “proper” grammar, leaving little room for linguistic diversity, rather than helping students develop their critical thinking skills. Students who are willing to change are then promised acceptance and recognition from colleges and universities. Why isn’t anyone asking these institutions to change for these students instead?

Where It Is Going:

In Jeffrey Cohen’s Monster Theory: Reading Culture, he argues that: “Monsters ask us how we perceive the world, and how we have misrepresented what we have attempted to place. They ask us to reevaluate our cultural assumptions about race, gender, sexuality, our perception of difference, our tolerance toward its expression. They ask us why we have created them.” When I say that I hope this project has a life of its own, I mean it. I am hoping that this project demands its readers to think critically about the education system in the US as students, educators, and policymakers. This process, as most monsters do, might scare them, but that’s all the more reason to do this kind of work. Below are some texts that have helped me start that work. I hope you find them useful too.

- Bettina Love—Teachers, We Cannot Go Back to the Way Things Were

- Bettina Love—We Want to Do More Than Survive: Abolitionist Teaching and the Pursuit of Educational Freedom

- Bettina Love—Dear White Teachers: You Can’t Love Your Black Students If You Don’t Know Them

- Sasha Costanza-Chock—Design Values: Hard-Coding Liberation?

- Asao B. Inoue—Labor-Based Grading Contracts: Building Equity and Inclusion in the Compassionate Writing Classroom

- Jacqueline Jones Royster—When the First Voice You Hear Is Not Your Own

- Conference on College Composition and Communication—This Ain’t Another Statement! This is a DEMAND for Black Linguistic Justice!

- Caitlin Gunn—Black Feminist Futurity: From Survival Rhetoric to Radical Speculation

- Octavia E. Butler— Parable of the Sower